A leadership that began to be polished when he was 11 years old, when he went to live in a boarding school to study, the president of the Administration Conseil from the Brazilian Institute of Agricultural Aviation (Ibravag), Júlio Augusto Kämpf has always been an institutional aggregator. And he took this enthusiasm to the professional field, had been participated in the founding of the entity who he now presides since 2018, as well as in the founding of the National Syndicate of the Agricultural Aviation’s Companies (Sindag), where he participates since 1997, including three and a half generations in the presidency.

His trajectory in agricultural aviation began by accident. Passing by the building of the Aeroclub’s secretary from the Brazilian city Cachoeira do Sul, city where he was born, he decided to learn more about the course to become a pilot. On the occasion, he was between 16 and 17 years old. The passion for aviation was born in the living experiences. Determined to enter the agricultural aviation, Kämpf is one of the remaining from the extinct “Cavag da Fazenda Ipanema” (AgAv course in a farm in Iperó/São Paulo), a place he keeps so many good memories and friendships of a lifetime.

Big defender of the sustainability of the activity, the diligent understands that the sector is fundamental to guarantee national productivity. He also defends the inclusion of tools in the public policies to control vectors and to combat fires. For it to occur in an adequate way, he understands that the scientific researches are fundamental and waits that they could be boosted by the approximation between Ibravag and the universities and research centers.

This process has to, in his view, come accompanied by education, contemplating the knowledge transmission, communication and development of technology, the tripod of Ibravag. Only then, he thinks that the sector could keep the protagonism of its history and become a reference to other countries.

You made the Cavag (Agricultural Pilot’s Course) in the Ipanema Farm?

Yes. That was in the second semester of 1982. The moment of the test for an agricultural pilot driver’s license was really tense, because I was defining my professional future. “Is it going to work? I am throwing all my cards here”, I thought. In the end, it was in my blood, I was already flying.

You were a student of José Carlos Christofoletti and Deodoro Ribas, two legends of the agricultural aviation. How was that?

It was exciting. The time I spent doing my Cavag, the course coordinator was Christofoletti. Then, the “Cenea” (National Center of Agricultural Engineering, a part of the Agriculture, Pecuniary and Supplies – Maps – as well as the responsible for these courses of AgAv formation , flight coordinators and agricultural technic) was going to make some changes. Right after I graduated from Cavag, there was a transfer of land, and the project to train professionals in agricultural aviation was slowly dismantled. I took classes with Christofoletti and Ribas. I learned a lot from both of them. In fact, the two teachers I had at the time have already received the Agricultural Aviation Merit Medal (a distinction awarded by Sindag). It was a period of great learning at Fazenda Ipanema.

Before you took the Agricultural Pilot’s Course, you began to study in college Business and Sociology. Although you did not finish them, do you believe they explain your vocation to institutionally enhance from throughout your life?

Without a doubt it gave me a certain base, a bit of culture. But this begins way earlier than college. I left home early. When I was 11 years old, I was in boarding school to study. From there, in a class with 80 or 90 other kids, you needed to be strict. Therefore, a natural leadership grew in me. Also, when I returned to my hometown, Cachoeira, I was the student council of the Barão do Rio Branco School. In 1985, already three years in the agricultural aviation field, me and some friends created the Agricultural Pilot from Rio Grande do Sul Association (Aspargs, in Portuguese). At the time, there was another group here in my state called Applicator’s Association (Assupla, in Portuguese), that was for entrepreneurs. Both entities always had a great relationship. It was something very intelligent, because the whole sector had an upgrade.

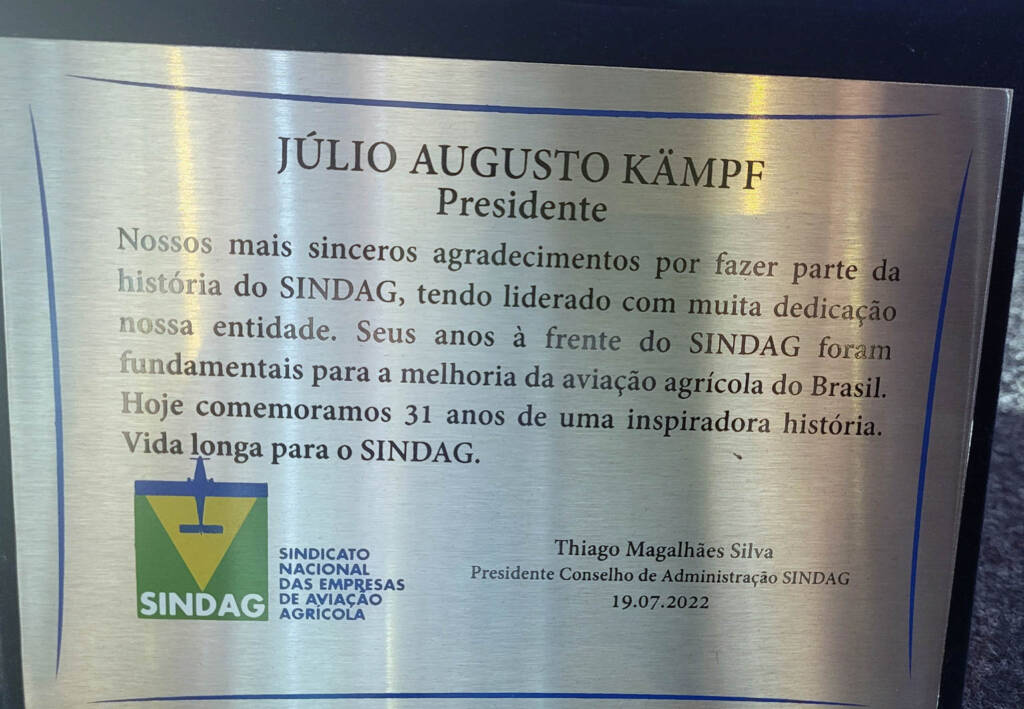

Later, as an entrepreneur, although you did not participate in the founding of Sindag, you helped to structure the entity, including the conquest of its own place/ office?

Sindag was founded on July 19, 1991. It had previously been a federation. The union’s headquarters were in Brasilia, but it was already operating in Rio Grande do Sul, supported by the structure of Assupla, and the mobile office (a trailer) of the president at the time, Euclides de Carli (1993/1995 and 1995/1997). In 1997, a group of aero-agricultural operators felt the need to bring the organization’s office to Porto Alegre/RS. I joined Sindag in 1997. The president at the time was Telmo Fabrício Dutra, a great mentor to the sector. I remember that we, plus Francisco Dias da Silva, Kiko as he is better known as, were in Porto Alegre with cardboard boxes full of documents, looking for a place to store them, because we didn’t have the money to pay the rent for an office. We later found a place with the late Terezinha Rocha, who was our first secretary. She had an accountancy firm and provided services to various aero-agricultural companies. So she had a lot of knowledge about agricultural aviation. Soon after that, Maria Eneida Miguel, who is also deceased, came in and started supporting us. Those were difficult times. Telephones didn’t exist in the countryside of Brazil. Everything was by letter. This was a period of consolidation for the union, and the statutes were even revised.

You, Carlos Heitor Belleza and Nelson Antônio Paim were presidents of Sindag three times each. How do you evaluate this period?

I’ve always been on Sindag’s board to collaborate. I was president three times plus half of Nelson Antônio Paim’s (Poxoréu) third time in presidency. My participation was continuous, regardless of whether I held a position on the board or not. I was also on the board of Carlos Heitor Belleza and José Ramon Rodriguez de Rodriguez, who were great presidents of Sindag. They expanded relations with government bodies, especially with MAPA and DAC (Department of Civil Aviation), now Anac (National Civil Aviation Agency). Under President Nelson Paim, the congresses were consolidated and began to raise the profile of the sector, increasing the number of members and making it possible to hire professionals. I remember that in the beginning, we often held meetings and didn’t even have enough quorum to sign the minutes. Today, it is very gratifying to see that Sindag has 235 member companies, practically 90% of the active companies in the sector in Brazil. It’s satisfying to see the interest of operators collaborating and helping the union to grow. Currently, Sindag has a very strong visibility within Brazilian agribusiness. This union is recognized for its material, for its attitude, for the work it has already delivered, for its participation in society. This is a source of pride for the entire category.

Photo: Personal collection

Ibravag comes as a reinforcement. How was the institute born?

Ibravag has a long history. There was a gap in Sindag due to union legislation, which made it impossible to raise funds to expand the range of activities. At the same time, farms began to acquire agricultural aircraft for use within the property, the so-called private operators, who now number a significant number within Brazil. From that, we had the idea of creating this institute to cover private aviation and thus, together with Sindag, be able to embrace the entire agricultural aviation chain. Drone and aircraft application companies can join in Sindag. Private aviation, as well as agronomists, pilots and individuals, fall under the umbrella of Ibravag. This institute is based on three pillars – education, communication and technology development. We are now working hard on knowledge transfer, which we consider to be the basis of the sector’s sustainability. To this end, in 2022 we signed a partnership with the Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (Sebrae Nacional) and launched BPA Brasil. The Good Agricultural Practices program focuses on the administrative and operational management of companies. Another project we are developing is in the area of communication with society. The Agricultural Aviation Magazine ( Revista AvAg) was launched in 2018 to improve our communication with society, explaining the effectiveness of the tool and the methods adopted. The urban population often has little knowledge of agriculture as a whole, especially of agricultural aviation and its benefits. The sector has had its image associated with the poisoning of people and the environment in a very mistaken and damaging way. By the way, the word agrotoxics only exists in Brazil. We are accused of things that have been scientifically proven not to have happened. At the public hearing “Challenges and opportunities for agricultural aviation in the country”, held by the Chamber of Deputies’ Committee on Agriculture, Livestock, Supply and Rural Development (CAPDR) in Brasilia, on August 30 this year, experts pointed out that most of the accusations are hidden behind environmental issues, when in fact they are driven by ideological and economic factors and a lack of scientific knowledge. Brazil is going to be the largest grain producer and exporter in the world, because it is the country that has fresh water and land to develop. It is also a country that has knowledge, a strong agricultural society with cutting-edge technology, which has grown dramatically over the last 30 years. One of the great promoters of this Brazilian agricultural project was Alysson Paolinelli*. He created Embrapa (the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation) and agriculture in the cerrado (Brazilian biome). There is no country in the world with a tropical climate that has this kind of production and environmental control. So we’ve grown a lot and today we’re exporters of technology, both in equipment and in application. The world is watching us. In fact, many groups and universities have begun to study the field, which has led to major developments in agricultural aviation. And one of the benchmarks for this is Brazil.

*Alysson Paolinelli (1936/2023) was Minister of Agriculture from 1974 to 1979. He is the interviewee in the first edition of AvAg Magazine – August 2018).

You have always been at the forefront of these issues involving new technologies, in search of safer and more sustainable agricultural aviation. What motivated you to pick up these fights?

The year I started flying, 1982, we already had some technology, but we were flying almost insanely. The aim was to fly very low, we had to almost touch the wheels of the aircraft to the ground, and that ended up being dangerous, tiring, adrenaline always running high. Over the years, we realized that this couldn’t work. It was very tense. There weren’t many rules, standards or prevention measures. I was always looking for greater profitability for the airplane and greater operational safety and results. At a certain point, I met some people from England, from the Micron Group, and I set them a challenge: “make some changes to my company’s working style”. They accepted this challenge and spent 30 days in Cachoeira do Sul, testing and perfecting equipment, as well as carrying out studies. The team gave me a lot of knowledge. It was a great time. I started studying again. I wanted to know more and more about aviation, about droplets, improving equipment, flight safety, greater aircraft productivity, and how to get the best out of it, because it was the time of one of the many crises in agriculture. Other colleagues here in Brazil were also looking for outsiders to listen to new proposals and methodologies, as well as issuing challenges to researchers. And the provocation was positive. People began to move more quickly and saw that they needed to evolve. And today Ibravag plays this role of bringing agricultural aviation closer to universities and research centers so that new names emerge within Brazil with knowledge of pulverization technology.

Photo: Castor Becker Júnior/C5 NewsPress

One of your flags was the inclusion of agricultural aviation in public vector control policies, based on the success of the 1975 application on the coast of São Paulo. What is missing for this idea to become a reality?

We have to think that vector control is in our legislation as a prerogative of agricultural aviation. Of course, I didn’t take part in this project in 1975, but my mentor Eduardo Cordeiro de Araújo was coordinating the program in Baixada Santista, and José Carlos Christofoletti was also involved in this operation, which involved several institutions in the state of São Paulo. It was to combat the Culex mosquito, which transmitted encephalitis. This work was pioneering here in Brazil and was successful. Everything is well documented scientifically, but the subject has been forgotten. I took up this debate again with agronomist Eduardo Cordeiro de Araújo (former agricultural pilot, former businessman, one of the most influential personalities in Brazilian agricultural aviation and advisor to Sindag and Ibravag) around 2002/2004. For several years, we talked to various institutions, especially the Ministry of Health. Unfortunately, they weren’t very receptive. Then, under Michel Temer’s government, Law 13.301/2016 was passed, which allows the use of agricultural aviation in epidemics, provided it is scientifically proven to be effective and authorized by the competent authority. Well, in this case, the competent authority is the Ministry of Health and, to prove it scientifically, we need to do research. Since then, we’ve been trying to establish partnerships with universities, Embrapa and the most diverse institutions to carry out scientific research into vector control and create a national protocol for emergency cases, like the one that was drawn up to combat locusts and delivered to the Ministry of Agriculture thanks to Sindag’s efforts. I insist on drawing up a protocol, because the document makes it clear what the operation will be like, which technologies to use, which equipment will be most effective, which entities will be involved in the operation and also which entity will control the numbers, that is, record the effectiveness of the work carried out.

Photo: Graziele Dietrich/C5 NewsPress

This year, you took part in the 18th St. Augustine Arbovirus Surveillance and Mosquito Control Workshop in March, sponsored by the Anastasia Mosquito Control District (AMCD). What was this meeting like?

I had the opportunity to take part in this meeting, where scientific papers on vector control from all over the world were presented every 20 minutes for three days. To give you an idea, in the United States they are studying mosquito control in the Arizona desert, the United States Navy itself has major studies on repellents – at first I thought this was funny – but then you realize that you can lose a war because of a flea infestation or because of scabies inside an aircraft carrier that is at sea for long periods. That’s when I realized the magnitude of the work that the army also does to control vector-borne diseases. A lot of research from Vietnam, Thailand, the Orient and the United States was presented. American society does not accept mosquitoes and demands that the state intervene when the insect starts to proliferate. In Central America, several countries use aerial spraying to control vectors, such as the island of Trinidad Tobago, Cuba and Mexico. And the population calls on the government for this control. And there’s public and private control too. It’s very interesting how concerned they are about this and how much they invest. I regret that Brazil is not making progress on this very important public health issue. According to a report by the Ministry of Health, in 2019 more than 5,000 cases of microcephaly were recorded due to Zika (a disease transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito). This number has probably increased. In addition to the disease, there have been deaths.

Do you even advocate the use of biological products in vector control?

Today, there are various types of application, various technologies that can be used. We even have biological products that could prevent an epidemic. I remind you that when we use biologicals we always target the larva. To combat the adult insect, only chemicals, called adulticides, are effective. Of course, these products are authorized and produced within the specifications of the World Health Organization (WHO). I don’t see the country working on a preventive proposal. Embrapa itself, through Cenargen*, has developed some biological products to control larvae and we haven’t managed to get the Ministry of Health to promote scientific research into this product. Refusing to do scientific research is something I still don’t understand. The adoption of an aerial vector control protocol, in my opinion, could be developed in three fundamental stages: firstly, making the population aware of the importance of doing their part to prevent the proliferation of vectors; secondly, the State doing its part, which starts with basic sanitation; and thirdly, the State developing public vector control policies, using preventive applications of larvicides and in the event of an epidemic, adulticides, by means of agricultural aviation.The results of worldwide surveys archived by Ibravag demonstrate the tool’s effectiveness. Other countries use helicopters, airplanes and ground equipment to control the insect. Here in Brazil, aerial applications would also be appropriate, especially given the number of vacant lots and hard-to-reach places within cities. In addition, the speed of the airplane allows an area of 3,000 to 4,000 hectares to be covered in up to two hours, at the best time according to the vector’s biology. So, in just a few hours a day and doing sequential work, in just a few days we would have a very efficient control of these disease transmitters.

*Cenargen – National Center for Genetic Resources, created in 1974 by Embrapa and recently renamed Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology.

We’re not talking about chemical products here. In your first term, 2007/2009, was there already talk of biologicals to combat the yellow fever transmitter?

Yes, you can control yellow fever and other diseases too. But we have already been to the city of Rio Branco, in Acre, where there is a high incidence of malaria and many cases of dengue, with the idea of carrying out a scientific study together with Cenargen/Embrapa, to see the effectiveness of biologicals applied by aircraft in that region. However, the study was not authorized. Since then, we haven’t been able to carry out any scientific research. It is obligatory, morally or scientifically, for the competent authority to take part in this project. The Ministry of Health should collaborate in some way so that research can be carried out.

And this rapprochement with Cenargen to discuss vector control didn’t come to fruition, but was this an opening for the development of Redagro? Was this project already a vision of the future?

No. Although Cenargen is within Embrapa, this was a matter for Embrapa, which is recognized the world over when it comes to biological products and development. There was a time when Embrapa was doing little research into application technology. So we made a proposal to bring Sindag and the research company closer together in order to develop a major knowledge transfer project for both parties. This approach resulted in several studies in Rio Grande do Sul, Mato Grosso and Paraná, and the conclusions were positive. Perhaps we should have continued researching, working constantly on application technologies, from the costal, to improve the equipment, which is undoubtedly the most dangerous model in terms of contamination of the professional, because the product is directly on the person’s back and with very little protection. I believe the drone will replace this manual labor. We have to evolve. The products are evolving. We are currently working a lot with bio-inputs. I was at Embrapa Meio Ambiente – Jaguariúna, and Evaristo de Miranda was head of that unit at the time and then he did that magnificent report on the preserved area of Brazil and the municipalities. And at the time, there was already talk that in the 2020s biological would explode in the world, that this was a process that had no turning back. The industry was already investing a lot of money at the time with this future in mind. And today we have several biological products being applied. It’s a transformation, it’s a change in technology, which we need to monitor better, researching how to get the best out of these products.

So Ibravag is now an arm of Sindag focused on communication, education and technology development. Can these studies on the use of airplanes in vector control be resumed in Ibravag’s work?

As I’ve already said, we’re getting closer to universities and other organizations in order to expand these research centers. However, this also depends on capital investment. I believe that a lot can evolve, that we can create new methods and controls. We have some interesting challenges, such as increasingly effective drop control. The technology for this already exists, but we need to keep improving and pass on this knowledge to everyone involved in the aerial farming operation, including ground staff.

Photo: Castor Becker Júnior/C5 NewsPress

Ibravag is heading into its fifth year of foundation and has already made the largest contribution of funds in the history of agricultural aviation in Brazil to a single project – the Good Agricultural Practices (BPA) program. Does this show that the sector was in need of an organization that could pass on knowledge?

In a way, yes. We on Sindag’s board and the other members had already been feeling the need for training courses to fill gaps left in previous courses. For example, some pilots had no knowledge of how to adjust an airplane’s bar, because this is often not a determining factor within an aviation school, but at the end of the day, in the field, especially on private properties, it can cause problems. Even agronomists had little knowledge of application technologies. We carried out a survey which showed that of the 512 agronomy schools in Brazil, perhaps ten devote subjects to spraying technologies. So this shows that there is a knowledge gap to be filled. So that’s the challenge we have within Ibravag: to increase the knowledge of professionals in the sector. We are even starting an agreement with Confea (Federal Council of Engineering and Agronomy). With this, Brazilian aviation, which is already recognized worldwide, will perhaps become a global example to be followed. In short, Brazil can play a leading role in these matters, but it needs researchers, institutions that get involved, and private entities to fund and collaborate with this research. For me, this is the model that marks the development of a nation. Today, in Brazil, the opposite is happening. The first thing people talk about is banning, instead of working scientifically on a technology, doing research to reduce the impact of the activity on any system. Prohibition is not evolution; prohibition, to me, is a step backwards.

Photo: Jane Catarina de Oliveira

You spoke earlier about the issue of transmitting knowledge. The institute was born with Aviação Agrícola magazine, which communicates with the external public, one of the major obstacles in the agribusiness sector as a whole. The magazine is five years old and has been renewed with a more forceful editorial line. Why is that?

I think it’s a natural process. When Ibravag’s Board of Directors started this project, it was in a modest way, but with very good but conservative content. The magazine gained visibility within society as an honest, transparent publication, bringing scientific articles, reports with specialists and respected personalities in the agro sector. After five years, the difficulties and problems have also changed. And we feel that the magazine is now mature enough to position itself a little more politically within the Brazilian scene. The time has come to renew it, so that it also has greater penetration in urban society. The time has come to take a stand on controversial issues that attack Brazilian agriculture, especially agricultural aviation.

You have hit hard on the issue of sustainability and the need for the agricultural aviation sector to contribute to food security. What is the trend in agricultural aviation nowadays?

Brazil is one of the main players in global agribusiness and, by 2030, Brazilian agricultural production is expected to grow by more than 20%, according to research by the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply (MAPA). Therefore, thinking about sustainability throughout the production chain and food safety is the reality of all Brazilian producers, it’s part of everyday life. And agricultural aviation, as an important part of this production chain, needs to constantly evolve. Companies that adopt strategies and business models aligned with the best ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) practices will differentiate themselves in the market and lay the foundations for their growth. The sooner a company prepares to face this challenge, the greater its chances of success. This is one of the pillars of our Good Agricultural Practices (BPA) project. To train agricultural aviation companies in nine pillars of action, including: business management, governance, sustainability and operational safety. When we talk about trends in agricultural aviation, we can talk about new technologies, Artificial Intelligence (AI), the study of plant genetics, the use of biologicals, the significant advances in meteorology and how all of this, when properly applied, helps our sector and precision aerial application. The fact is that the future is unimaginable. However, there are some trends that we can predict and anticipate. And all of this involves good company management.

Why is there this avalanche of requests to ban agricultural aviation, including in municipalities, considering that the same products applied by tractor are applied by plane? Why is agricultural aviation the villain of the story?

It’s like I said before. The tool is being attacked as if it were the cause of the controversial “contaminations”. It’s an ideological issue, based on economic and geopolitical interests, disguised as a global environmentalist agenda. We are torpedoed with constant criticism for the way we conduct our internal environmental policy. However, we have environmental/forestry legislation that does not exist anywhere else in the world. We need to recover our identity as a nation in order to grow. In my opinion, the country should be thinking about promoting development, employment, social conditions for the population, good quality food, and wealth. That’s the way to make a nation sustainable. Brazil is still selling products and wealth in natura – soybeans, iron ore, cotton feathers, live cattle, we could be selling industrialized products. This would bring fantastic social quality to the country. Thousands and thousands of jobs would be created. While we are discussing the levels of pesticides used in Brazil, products that have been widely tested, authorized and regulated, 35 million people in Brazil live without treated water and around 100 million do not have access to sewage collection, resulting in preventable diseases that can lead to death from contamination. Only 50% of the country’s sewage is treated. I think it’s time we started talking about these challenges and proposed solutions.

Photo: Castor Becker Júnior/C5 NewsPress

Where is agricultural aviation heading? And what can we expect in five or ten years’ time?

It is moving towards being an example of technology, knowledge and science. Brazil needs coherent legislation and the sector needs legal certainty to move forward. That’s why we have the BPA (Good Agricultural Practices program), which goes through all the processes of an agricultural aviation company. There’s no point in having cutting-edge technology if you have inadequate management. One thing leads to another. You have to grow at all levels. From personal relationships to commitment to society. This is the path that agricultural aviation will inevitably have to take. Without this global management adaptation, operators won’t be able to use cutting-edge technology at the end of the day. This is a chain. You have to evolve as a whole. You have to have your members, your teams integrated into this process. This is the sustainability of an activity.